Biography

“Кохай хлопця, хай росте Україні на славу”

“Love the boy, that he may grow for the glory of Ukraine.”

Yurii Stepanovich Kodak (1914-1991) was born in Myrhorod, Poltava, Ukraine in a part of Myrhord which is one of the oldest settled areas of Myrhorod mentioned as such in 18th century town documents. For a long time, Myrhorod was considered to be the true heart of Ukraine. As early as 1832, the Ukrainian national fair, Sorochynsky Yarmarok was held in the fields near Myrhorod. The writer Hryhori Hohol lived in Myrhorod, and in following decades, other famous Ukrainians as well – several of whom lived on Vulytsia Lazarenka. The dwellings may have been peasant-like but the people living in them were not.

The area of Vulytsia Lazarenko and its neighbouring streets were more village-like in attributes than a town or city. The dirt lanes were bordered

by individual single-storied white cottages, surrounded by sheds, pens, chicken coups, always a large garden and, occasionally an orchard. Geese roamed the dusty lanes, then, and even in the 1990s. It was in this village, in the “selyanska hata” at number 18 Lazarenko Street (formerly Chepajeva) that Yurii was born and raised.

Yurii was the only child of Kylyna Dubyna (1893-1984) and Stepan Panasenko whose writer’s pseudonym was Vasylchenko. Kylyna was from a Christian family as indicated by the fact that she was given the name Akulina, the Saint for May 26th, her birth date. However, Kylyna was the name she used throughout her life.

Kylyna’s parents were Myhajlo Stepanovich and Paraskovija Dubyna. Her father was a kozak while her mother was a prize winning weaver. Kylyna had one brother, Petro and several cousins – who, as was the practise in Ukrainian families at that time, were called sisters. The family was very musical. One of the sisters when hospitalized would sing folks songs from her hospital bed, and people would gather under her window to listen. Yurii’s various Dubyna aunts and cousins played a large part in his upbringing during the years when Kylyna was living in Kyiv with her husband, Vasylchenko. In 1968, in commemoration of the 90th anniversary of the birth of Stepan Vasylchenko, Kylyna was allowed to leave Myrhorod, Ukraine and visit her son in Ottawa, Canada, a reunion after almost 40 years of forced separation.

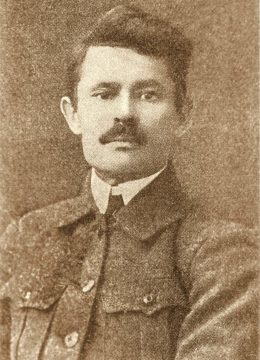

Yurii’s father, Stepan Vasylchenko (1879-1932) was born to a poor peasant family, in the village of Ichnia, Chernihivska Oblast. He had four brothers and one sister, Lizaveta. The mother and all the children worked for others, not owning any land of their own. Vasylchenko’s father, a cobbler; however, was literate and encouraged his six children to study and to learn because as he said, there was no inheritance that he could give them. In addition to the village school, the children’s education was augmented by them memorizing Taras Schevchenko’s works, the epic stories of the kozaks and Ukrainian fairy tales.

Stepan’s success in school was exceptional and he was able to leave the village for higher education – the first young student in his village to do so. He became a teacher, then a writer and journalist. As a teacher, he was remembered for never having lifted a hand against a pupil, and for imparting to his students a sense of joy in learning. He is remembered also for the free evening classes he initiated for the parents of his pupils, teaching them how to read and

write in Ukrainian. At least one school in Ukraine’s Donbas has a room dedicated to Stepan Vasylchenko for his vision of universal literacy.

In 1905, Vasylchenko’s teaching career was curtailed by order of the Czarist regime. He was sentenced to two years in Bahmut prison for counter-revolutionary activity: organizing and instigating, workers and students to strike in protest against the ruling autocracy. He was released after 18 months and ordered never to teach again.

Forbidden to teach,Vasylchenko turned to writing short stories about children, the “seljany”(peasants) and his experiences while travelling and while in prison. His short stories, The Aviation Club, Svekor, Prybluda, Roman, In the Weeds, Gypsy, and The Naughty Jug testify to his deep understanding of a child’s psychology.

In 1914, Vasylcneko entered the army and served as commander of a Strategic and Tactical Unit on the Western front near Peremysh (Przemysl, Poland). Post-war period found him working as a journalist for the liberal-leaning Kyiv newspaper, Rada.

Kylyna’s family of cousins was very musical, and Stepan shared this love of and interest in music. In 1920, he joined the First Dniprosoyouz Travelling Choir as a journalist to record the travels and experiences of this group whose aim was to counter the course, ribald songs of Lenin’s time by raising awareness of Ukrainian folk and opera songs.

According to Vasylchenko, the trinity that inspired his writing was the Kobzar, the works of Hohol and the Ukrainian song. His writing has been described as impressionistic but grounded in realism, poignant yet optimistic. Vasylchenko died August 1932, his heart broken by the enforced genocidal famine (Holodomor) inflicted upon the people he loved.

Early Years

Yuri’s childhood was carefree, especially so since he was raised by his mother’s cousins, rather than Kylyna who, after Yurii started school, went to live in Kyiv to support her husband in his career. Yurii’s childhood could have been that very same experience as depicted in his father’s book “In The Weeds.” except he was not alone like young Taras Shevchenko, but was accompanied by his lively imaginative cousins, his brothers as he called them. Summers were spent outdoors, winters on the “peech” a gathering place where stories were told and games were invented and played. And, although adventures and misadventures and childhood pranks were frequent, as Yuri told his family, not one finger was ever lifted in reprimand against him. His aunts as his custodians felt it was not right to punish any child except their own.

Education & Student Life

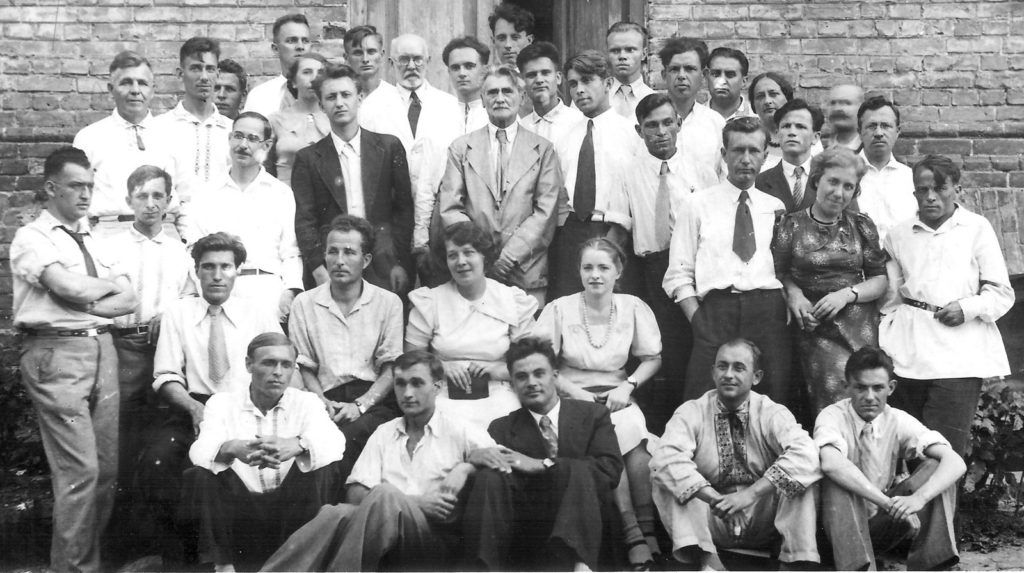

Yurii completed seven years of elementary school in Myrhorod, then went to Kyiv to live with his parents, to attend the Polytechnical Institute from 1930 to 1934. He majored in Construction; the final year was devoted to practical field work. Photo: A Summer Surveying Class. Yurii, 2nd row, on right.

At the Kyivan State Institute of Art, he was taught by V. H Zabolotnyj who designed the Verhovna Rada building in Kyiv, P. H. Yurchenko and Vasyl Krychevsky. From Krychevsky, Yuri adopted the folk-centred approach to architectural design. Buildings were to be to human scale, never overpowering, and elaborated where possible with folkloric themes. Yurii greatly admired Krychevsky and from him adopted his lifelong habit of wearing only light-coloured suits. Similarly, when he finally began working as an architect of churches, in the Diaspora, he always used light-coloured materials. (In only a few cases did the parish’s wishes override this preference) Brick and especially reddish brick he avoided, as this was not an exterior colour used in churches of his native Ukraine.

Politically, the years between 1925-1929 were fairly stable for Ukrainians, and Yurii’s schooling progressed normally. He did not receive high marks however, because too often his building designs featured fountains or rooftop gardens which were deemed to be bourgeoisie and not conforming to socialist realism. In 1929, Stalin’s oppression against Ukrainians began to be felt. On the occasion of the May Day Celebration, Yurii and his fellow students, under the threat of pointed rifles and bayonets, were forced to work through the night repainting the flowers on a huge banner, from yellow and blue, to yellow and black. On another similar occasion, the students were accused of conspiracy because one of the faces in the banner resembled Trotsky. In 1932, when Yurii’s father was dying in Myrhorod, Yurii was deliberately, not informed by his teachers until several days after the funeral of his father.

1940s & The War Years

June 1940 brought with it graduation day and shortly after that, without ever having a chance to practice his profession, Yurii was drafted into the Red Army. He endured the rigours of army life with his close friend and colleague from the Art Institute, Vasyl Tomashevsky. Eventually, they were both captured and interred in German POW camps, albeit different ones. And similarly to the hero in George Mendelev’s movie Bitter Harvest, for both Yurii and Vasyl it was their abilities as artists that saved their lives. In exchange for painting the portraits of the guards’ wives, children and relatives, they were given extra rations. This allowed them to survive the meager diets given to captured Slavs. When Yurii contracted typhoid, his prisoner status was further improved for he was transferred to a German hospital for American POWs.

Once recovered, Yurii was moved to a slave labour camp where his trained skills of drafting were put to use. At this camp, he met his wife, Natalie who had been taken prisoner while escaping the Siege of Leningrad. In June 1945, defeated Germany was in disarray and prisoners now free, were scrambling to get to the west of Germany and into the American zone to avoid capture by the Soviets. Yurii, and his wife Natalie found themselves first in Bamberg, Bavaria, where their child was born, then in the DP (Displaced Persons) camp in Bayreuth, also in Bavaria, Germany.

In Bamberg and Bayreuth, as in all the other DP camps, the refugees re-created as much as possible their lives prior to the war. Church services, newspapers and publications, athletic competitions, theater groups, choirs, dance groups, art exhibits, and schooling at all levels were established and conducted. Yurii gave art lessons, painted back-drops for the theater productions, designed and built his first iconostas, and took part in numerous group art competitions, winning First Prize and 3,000 Reich Marks for his portrait of “Girl with Flower.”

In preparation for emigration out of the DP camp, the Testing Commission of the Preparatory Commission for the International Refugee Organization, assessed Yurii as an architect. Having no sponsors, Yurii went to work in Canada under a labour contract which meant that he had to leave his wife and child behind, in Bayreuth.

He sailed out of Germany on the ship “Swallow,” on August 8, 1948 and arrived 8 days later in Halifax; from there he was transported by train to Freeman (Burlington), Ontario. Yurii immediately applied for work at Stelco, Hamilton’s steel manufacturing plant but was turned down as being too thin. However, he was accepted for work hauling bricks, and later was “promoted” to masonry work. The work was physically demanding, and the living conditions made the work even more difficult. Six labourers, all immigrants were housed in a one room building with no heat or running water.

Fortunately, one day while walking the streets of Hamilton, Yurii heard the Ukrainian language spoken. He stopped the stranger and the conversation that ensued changed the course of his working career for he then became a member of the Ukrainian/Canadian community of St. Vladimir’s Ukrainian Orthodox church and this opened doors to the church building boom that was under way throughout the Diaspora.

In August, 1949, a year after arriving in Canada, Yurii was Certified as having discharged the terms of his labour contract with Canada and he therefore applied for reunification with his family. After six months of uncertainty, permission was granted. On January 5, 1949 Yurii paid The International Refugee Organization (Canadian Office) $40.00 for the airfare, and on February 4, 1949 his wife and child arrived at Hamilton’s mountain airport.

Life In Hamilton

Yurii Kodak liked to say that he was born twice. The first time was his natural birth in Myrhorod, Poltava, the second was when he arrived in Canada. This second life, beginning in Hamilton was free of fear, repression and restrictions, and was full of opportunities for self-expression through work, art and community involvement.

In Canada, Yurii was able to design and build the kind of churches that he had long admired as a student in Kyiv, the very same churches that subsequently were routinely demolished by the atheistic Soviet regime. In 1934, he had witnessed the three-month long dismantling of the beautiful 12-domed Michaelivsky Sobor. His artistic nature cried out for a restitution of that beauty, and of so many other churches in his homeland. But, not there. Only in Canada could he achieve that which he never could have done in the country of his birth.

The Ukrainian-Canadian community in Hamilton was vibrant and energetic; full of talented and creative people, and Yurii participated in all the activities that the community had to offer. He joined the choir, played the guitar in the orchestra, took on roles in theatrical productions, including Nazar Stodola and Zaporozets Za Dunayem, and for a period of time, taught Sunday school.

He became a member of the “Ukrainian War Veterans League, Branch No. 7″ and Suzhero (Ukrainian Association of Victims of Russian Communist Terror) as well as TYC (Tovarystvo Ukraiintsiv v Kanadi) and, in 1952 served as President of St. Vladimir’s Parish.

Because community life was rich, little notice was paid to impoverished living conditions which, in the land of opportunity did not last long anyhow. The Kodak’s first home was one room in a row-house by the train tracks.  The second home was two rooms, and a kitchen shared by three other families, in the Napier Street house of Ilko Shkryblak. Physical living conditions may have been tight but relationships were genial and optimistic. Close ties, resembling family ties were further created by the naming of god-parents, for new-born children. These relationships lasted forever.

The second home was two rooms, and a kitchen shared by three other families, in the Napier Street house of Ilko Shkryblak. Physical living conditions may have been tight but relationships were genial and optimistic. Close ties, resembling family ties were further created by the naming of god-parents, for new-born children. These relationships lasted forever.

In 1952, thanks to a loan from Dr. Klimasko, the Kodaks, were able to purchase their own house at 76 Smith Ave. For this event, the church parish kindly gifted the family with a very necessary kitchen set of table and chairs which served the family for decades. Because the nature of his work, the contracts for architectural designs, the supervision of construction, and all the organizations and artistic groups with which he was involved, Yurii was rarely home. During the Hamilton period, Yurii was an absentee father and it was therefore, Natalie who raised the three children: Helen born in 1952 and Boris in 1953. It was she who kept the home fires burning. She literally shovelling coal into the central heating furnace in winter, changed windows with the seasons, kept an extensive garden, and put up large stores of preserves for the winter. She handled the finances, paying the bills, collecting rent from the three lodgers who lived on the second floor, and delivering each month to Mrs. Labrun the mortgage payment.

month to Mrs. Labrun the mortgage payment.

In 1951, on the occasion of Princess Elizabeth’s visit to Canada, Yurii designed and with other parish members built a float to represent the Ukrainian community in Hamilton’s Parade of Nationalities. Riding on the front of the float with his five-year-old daughter sitting on the platform behind him, was a proud moment for Yurii. He felt this parade, on his float built for Princess Elizabeth truly marked his citizenship. He was no longer a Ukrainian immigrant in a foreign country. He was a Canadian in his new homeland.

Life In Ottawa

In June 1956, The Department of Public Works had offered George Kodak a permanent position as architect in their Construction Branch in Ottawa. George accepted the position and began work in September of that year. The family followed. Natalie and three children, moved to Ottawa and set up house in a rented duplex steps away from the scenic Rideau Canal. The permanent position was a welcome change from the hectic task of free-lance architectural design work which involved a lot of travelling to other cities, and the time consuming but necessary preparation by hand of all architectural drawings. Every change or revisions had to be done manually with eraser and pencil. Contract negotiations, and design discussions were done also done by written correspondence. Bulky final drawings had to be sent by Canada Post. George did not employ a secretary, and so performed all these tasks himself. Thus, the family lifestyle changed dramatically with the move to Ottawa. The government position, and regular working hours meant George could finally become a family man.

In 1964, the family purchased their own house, a house which from the facade, resembled the village house in Myrhorod. It was white with stuccoed walls, had a low-pitched roof with two dormers and sat on half an acre of land which boasted a mini orchard of five apple trees. Perhaps because of its unassuming appearance and lack of capitalistic opulence, the officials at the Soviet Embassy allowed visitors from Ukraine to come to the house. The first of these was Yuri’s mother, who on the occasion of Stepan Vasylchenko’s 90th anniversary in 1969, was allowed to come to Canada, and to stay at the Kodak’s house for three months.

Other visitors from Ukraine followed, such as the singer Raisa Kyrychenko, Volodymyr Browchenko and Dmitro Pavlychko, and after Glasnost others, such as, poets Vasyl Herasemiuk and Ihor Remaruk, ecclesiastic specialist, Dmitro Stepovik, and writers Mykola Zulynsky, Ivan Dzyuba, Vasyl Skurativsky, Les Taniuk; and Yurii Bohayevsky. The reputation of Stepan Vasylchenko paved the way for these visitors to freely visit Yurii’s home where songs were sung, stories told and glasses lifted to toast peace and freedom for Ukraine.

The first family car was purchased 1963. This convenience made many leisure activities possible, such as vacations at a rented cottage at Clayton Lake where other Ukrainian families also vacationed, and fishing for the men. There were family trips to Atlantic City, Wildwood in New Jersey, North Miami in Florida, and Soyuzivka in Kerhonkson, New York . While visiting Soyuzivka, in 1985, Yurii reunited with fellow graduates of the Kyiv Arts institute, Ludmila Morozova and John Holton (Nakonechny) who lived nearby in Hunter, New York.

In 1987, George travelled to Ukraine with his son Boris, visiting the house on Lazarenko Street where he was born and raised, and his father’s memorial museum in Ichnia. In Kyiv he reunited with his other school day friends, architects, like Katernoha and Ivan Shevchenko.

When his wife Natalie died, George turned to painting and sculpting more fully. With his daughter Helen, he attended art classes at The Ottawa School of Art and took part in that school’s exhibitions. His own solo exhibition, under the auspices of Plast, was held in 1984 at St. Mary’s Ukrainian Orthodox Church. He painted murals for the Chernobyl commemoration, at that same church, and the stage backdrop for the Ukrainian dance production, “Ribbons and Swords,” which was co-choreographed by his youngest son, Ihor.

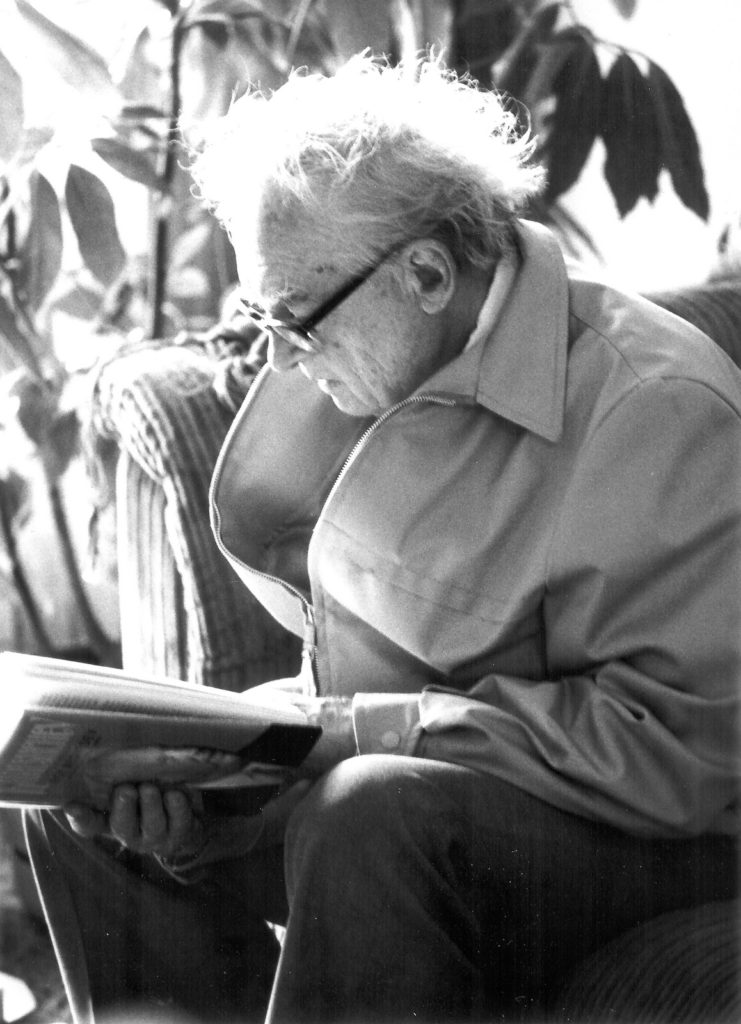

But art was not his only passion. Reading for the attainment of knowledge and understanding of Ukraine’s history, culture and language took up a lot of Yurii’s time. In particular, he was interested in ancient Ukraine, pre-Trypillian culture, the Cimmerians and Scythian cultures.

Studying the motifs in Scythian jewelry, and the words of Ukrainian kolyadky (carols) and pre-Christian haivky, he noted similarities of themes and recorded these in a paper (to be published).

Darwin’s book, “On the Origin of Species” and Pasternak’s, “Archaeology of Ukraine” were of also of great interest as Yurii Kodak was developing his own theory as to the origins of man’s consciousness and language, and that the source, of the proto-Indo-European language was to be found on the territory of Ukraine. The book, “Words, the Evolution of Western Languages,” by Viktor Stevenson articulates the same idea – that the proto-Indo European tongue originated in Ukraine, in the area of Poltava where Yurii was born. Today, this is an idea accepted by some – especially philologists in Ukraine but in the 1970s and 1980s it was not.

In 1991, when Ukraine declared its indepaendence, Yurii contributed his ideas and sketches to the first mock-up designs for the new Ukrainian currency, the Hrynia. They were then presented to the Speaker of the Ukrainian Parliament (Verhovna Rada) Leonid Kravchuk in Kyiv by Orest Nowakiwsky on behalf of the Canadian Bank Note Company. Negotiations conducted by Orest Nowakiwsky, Yuri’s son-in-law, resulted in the signing of a historic contract to print two billion Ukrainian banknotes in Canada to replace the Soviet Ruble.

His ecclesiastic work continued until his death. In 1991, the congregation of St. Vladimir in Hamilton turned to Yurii once again for a design of the front doors to the church. His design of St. Volodymyr and Knyahynia Olha was accepted. The doors were fashioned and executed in bronze in Kyiv, by Michael Andreyovych Dmitriv. The four bronze panels were transported to Canada and installed posthumously in 1993.

St. Vladmir’s church was Yurii’s first Canadian architectural work, and the doors for this church were his last ecclesiastical artistic achievement.

St. Vladmir’s church was Yurii’s first Canadian architectural work, and the doors for this church were his last ecclesiastic artistic achievement.